Fans of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy will remember Slartibartfast, the planet architect who was very proud of his award-winning design for Norway. The fjords, he explained, were designed to give the continent a “baroque” feel. And a fjord is indeed a very splendid thing. A fjord, by definition, is a long and narrow inlet to the sea, flanked by very steep cliffs, and carved by glacial activity. (Or Slartibartfast.) While Norway coined the name “fjord,” they have no trademark on the geological flourish. You will find fjords anywhere there are mountains that meet the sea, and freezing temperatures to support glaciers, including the coast of Chile, New Zealand, and the Northwest coast of North America.

First Prize!

From time to time I like to take electronic expeditions to rare places on Earth, to see what I can find. Readers know I have a passion for fractals, and subscribe to something I call Fractal Earth Theory; the theory that the patterns of the planet are self-repeating ad infinitum. It was thinking about the true lengths of coastlines that led Mandelbrot to discover fractals in the first place; fjords make for rough edges in the world, wrinkling the land into a series of nooks and hidey-holes in which any manner of animal might live.

Today, we look for the unique wildlife of the fjords. I use a basic set of hypotheses as a compass:

1. Wherever life can exist, life will exist.

2. Where ever a habitat is geographically separated in any physical way, unique life will exist.

3. The more severely isolated a habitat is, the greater the number of unique species.

Fjords, however unique as geologic structures, are not very isolated: their cliffs connect with the mainland, and their inlets connect with the ocean. Their main aspects of geographic distinguishment are the steep angles of their cliffs, on which only certain wildflowers can grow, and the murky, silty, brackish water below. Fjords are often estuarine, with freshwater running as a river into their channels, which will certainly exclude many sensitive saltwater animals. The turbid, murky water is caused by violent tidal action, which in turn is caused by the water rushing over the lip of the terminal moraine left by the glacier at the fjord’s edge; this turbulence may also make the habitat even more exclusive, and more unique. But all in all, a fjord is not as isolated as a lake or an island, and we can’t expect a great number of unique species. But a few, sure. Some modifiers to the original compass:

4. The cold temperatures and low salinity will lead to a lower general biodiversity for animals, compared to a tropical habitat.

5. The cold water, with its high level of dissolved oxygen, will nonetheless support a high overall biomass.

6. The prediction of high aquatic biomass makes it more likely that any unique species are aquatic.

With these in mind, we set out to explore the nooks of the fjords, seeking life found nowhere else on Earth. And what we’ll find is a series of ecosystems among the most mysterious and little-known in science.

Destination: Norway.

Unique Species: When you hear the term “coral reef,” what does it conjure? Probably a tropical paradise full of candy-colored fish and threatening sharks, an aquatic rainforest set in crystal-clear water. So it might surprise you to learn there are ancient coral reefs in the Norwegian fjords. Cold-water reefs are a massively important part of the ecosystem, acting as nurseries for the abundant marine life around the coast. The coral here are white, skeletal structures, lacking any of the symbiotic algae of their warm-water counterparts. The water is too murky, and the polyps often build their coral homes too deep, for the sun to directly power this ecosystem through photosynthesis.

A Lophelia pertusa reef in a Norwegian fjord. Not exactly “Finding Nemo.”

Lophelia pertusa and other cold-water corals are not endemic to the fjords, or even Europe. But because the Scandinavian coral reefs were so recently discovered, they are even less well-explored than the enticing tropical reefs. Scientists have found two unique species living together in a single fjord reef in Sweden: a painfully primitive worm-like creature called Xenoturbella, and a bacterium in its body cavity called Endoxenoturbella lovénii. Xenoturbella seems to be degenerated from the molluscs, and is truly one of the world’s simplest animals: it has no brain, no heart, and no guts. (Perhaps it should see the Wizard?) Additionally, it has no excretory system, no gonads, no senses, no limbs, and no real organs of any kind. It seems that this poor wretch lives entirely by the grace of its endosymbiotic bacterium, and does most of its living as a larva, when it parasitizes mollusc larvae from the inside. Still, the stupid little gummi worm has much to teach us about the origins of Animalia.

Behold! The Jewel of the Fjord.

Destination: New Zealand.

Unique Species: The fjords of New Zealand, found at the Southernmost tip, are called “sounds,” and bear evocative names such as “Dusky Sound” and “Doubtful Sound.” (Did you hear something?) Like the fjords of Scandinavia, these too have coral reefs, though arguably less macabre, despite the fact that they’ve exchanged bone-white coral for photosynthetic Black Coral. The Black Coral Reefs are home to a diverse array of colorful fish, dolphins, New Zealand fur seals, little blue penguins, and… wait for it… more interesting than a Xenoturbella worm…

the endemic Fiordland Crested Penguin. This timid bird breeds only along the fjorded coast of Southern New Zealand. You’d be correct to think that a fjord would offer superior protection for your flock — steep cliffs on one side, turbulent water on the other — but in this case it’s unclear why the penguin chose the fjords, as New Zealand has not had land predators outside of moas and kea parrots until modern times. But because they usually only lay one egg at a time, I suppose the stakes were high enough that they could take no chances. The fjords now offer too little shelter, as the weasels introduced from Europe have left fewer than 1,000 breeding pairs of penguins.

Destination: British Columbia.

Unique Species: The Northwest coast is a vibrant, frigid jungle of marine life. But it is somewhat less so in the fjords; the unusually high terminal moraines that stop up the entrances to the fjords can actually limit water circulation here, making them more placid than their Scandinavian counterparts and depleting their oxygen levels. Many fish will avoid fjords for this reason, though air-breathers like whales and seals can still enjoy the relative sheltered calm. One animal that has little problem with the low dissolved oxygen is the sponge, and the beds of the American fjords are often blanketed with sponge reefs.

The glass sponges of British Columbia are so called because the animals are composed of 90% silica. (After all those “glass animals” yesterday, here’s one that actually has as much silica as a windowpane.) Sponges are among the simplest of animals, and are mainly notable for their absence: whether free-floating motile creatures, or sessile coral-like colonies, their glass exoskeleton makes up most of their bodies. The “living” part is mainly a thin flagella to circulate water and a crude digestive system. Nonetheless, the 300 species native to British Columbia form spectacular sponge gardens which support crustacean and mollusc life. Pictured: the native cloud sponge Aphrocallistes vastus.

Destination: Chile.

Unique Species: Chile may be shaped like a hot chile pepper, but the southern tip of Patagonia is downright chilly. The water temperature may be frigid, but it’s stable, and stability is the foundation for evolution. That’s the first character of a fjord: stability and protection. Another theme is coldness and darkness, so that species found in the deep ocean, such as New Zealand’s Black Coral, are never found closer to shore than in a fjord. So, despite the fact that the Patagonian fjords are among the least-explored coastal ecosystems on the planet, there’s a high chance of finding a unique endemic species in the reefs.

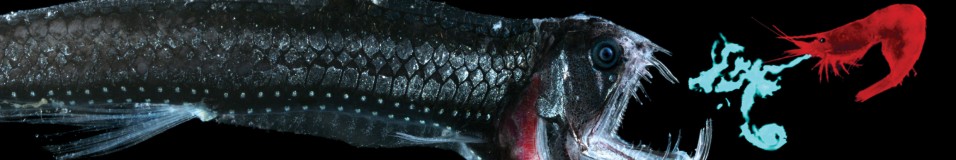

The zoarcid fishes, or eelpouts, are found deep in the oceans, including the hydrothermal vents which have no reliance on solar energy. And one rare Patagonian eelpout, Ophthalmolycus macrops, has come up from the bethic abyss and lives only in the Chilean fjords. It is so rare, in fact, that I had to use another picture of one like it: a little over a foot long, with a fused caudal and dorsal fin and a general eel-like appearance. Though first described in 1880, we’ve learned barely anything more about it since then.

That is the third component of fjords: mystery. In the murky shallows, where creatures from the deep can infiltrate the coastline and cold-water coral and sponge reefs stipple the floor, we have not begun to explore. Like the folds and wrinkles in the brain, fjords create intriguing niches in the coastline. The deeper we go, I expect, the more niches we’ll find, and the more unique animals we’ll find that call them home.

November 18th, 2010 at 12:46 pm

Wish to visit all of those places up close.So…what do they say in Ithaca, GORGE ous?

I love the language of this:

It seems that this poor wretch lives entirely by the grace of its endosymbiotic bacterium, and does most of its living as a larva, when it parasitizes mollusc larvae from the inside. Still, the stupid little gummi worm has much to teach us about the origins of Animalia.”

endosymbiotic bacterium & parasitizes mollusc larvae

🙂

And this

After all those “glass animals” yesterday, here’s one that actually has as much silica as a windowpane.) Sponges are among the simplest of animals, and are mainly notable for their absence: whether free-floating motile creatures, or sessile coral-like colonies, their glass exoskeleton makes up most of their bodies. The “living” part is mainly a thin flagella to circulate water ”

Fascinating flagella. 🙂

November 18th, 2010 at 12:57 pm

Sponges are still hard for me to wrap my head around, for some reason. They seem to me like haunted houses of glass.

November 18th, 2010 at 3:18 pm

http://www.flickr.com/photos/army_arch/3641272792/

November 18th, 2010 at 5:23 pm

Exactly! But there are hungry ghosts with whips in every window.

November 20th, 2010 at 7:32 am

Or maybe ghost-riding the whip. In a sponge, the door’s are open, the power’s off, and everybody’s outside moving.

November 20th, 2010 at 12:40 pm

Did you just make a hyphy-era hip hop reference? Win for you.