“Ugly food is good to eat.” You’ll find variations of that phrase in cultures around the world, particularly among cooks with a good sense of flavor and a lousy sense of decorative plating. Lumpy brown risottos with chunks of curious fungus might just be a truffle explosion, and properly-cooked soul food should arrive as one edible, semi-solid stain, falling out of the bun and preferably off the plate. The other day I found myself eating dinner with a friend of Korean descent, who cooked the gathering of friends a meal of bibimbap and stuffed kelp rolls that was both visually beautiful and gastronomically delectable. Offhand, I asked him what kind of fish was in the rolls. It was a dark, oily, muscular flavor; soft on the tongue but strong on the nose, deliciously assertive about its identity but frustratingly unfamiliar to me. “Monkfish,” he replied.

“Aha!” I said. “Damn, monkfish is good.”

We half-nodded in agreement.

“Pretty damn ugly, though.”

We half-nodded in agreement.

The next day, by chance, I ended up at the New England Aquarium, and was reminded that “pretty damn ugly” is an insult to pretty damn ugly fish.

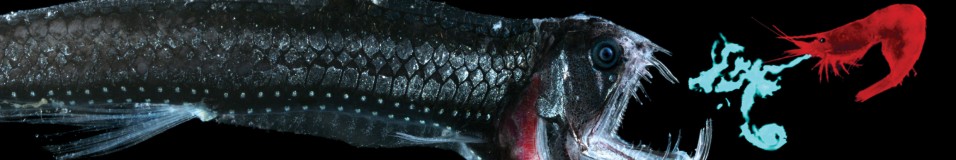

The American Monkfish, Lophius americanus, or the “goosefish” as it’s known locally, belongs to the anglerfish family and, in addition to the anglerfish’s lure, shares every bit of its rugged good looks. There are many recipes online that describe how to make monkfish dishes, but let me share with you the basic recipe for a monkfish itself:

1. Buy a pumpkin.

2. Carve the biggest, fangliest mouth on that pumpkin that you can.

3. Allow pumpkin to rot beyond recognition.

4. Drop a refrigerator on pumpkin, out of mercy.

5. Attach tail.

The pancake aspect of the monkfish allows it to ambush prey from the ocean floor, hidden in plain sight. The giant mouth allows it to capture and swallow prey as large as itself; monkfish will eat anything that gets within biting distance, including small sharks, diving ducks, and other monkfish, and there are reports of monkfish eating the wooden buoys of lobster traps. (The name “goosefish” doesn’t come from the flavor of the meat but for their penchant for swimming up to the surface to devour floating seabirds.) For most of their adult lives, they live quietly and patiently, insipid puddles of unkissable maw blending into the debris on the sea floor. But twice a year, the female monkfish balloons up into a half-pumpkin shape that makes her a little more conspicuous: call it a “baby bump.” And what she releases — and what the monkfish I saw that day had released — is anything but ugly.

Monkfish release their eggs as one long veil that floats to the water’s surface for one to three weeks before the salt dissolves the binding mucus and the eggs float apart. Each veil can be sixty feet long (though they are usually around 30 feet), can be two or three feet wide, and contain over a million eggs. Drifting along in the currents off North America and Northern Europe, they appear as lost mermaid scarves, in colors ranging from white to pink to orange.

Perhaps the phenomenon of something so excruciatingly homely creating something of such ethereal beauty is too easy. The question that occurred first to me is: if you were going to lay a million eggs, why would you pack them together into something so conspicuous? Other animals treat fish eggs — caviar, roe and the like — with much the same deference that we do: an expensive and epicurian delight that should always be eaten immediately if you can find it for free. So what possesses the monkfish to lay all its eggs in one basket?

Monkfish are hardly the only animals to lay their eggs in such profusion, but they seem almost unique in their confidence that their eggs can survive in plain sight. Most fish will either scatter their eggs, or build a nest and defend them. Like the Easter bunny, most fish will hide their eggs behind pieces of vegetation, or on the ground, usually buried in the rocky or sandy substrate. The Easter bunny does not simply leave a few hundred thousand cartons of eggs tied together for one very lucky child to find.

Some fish, known as mouthbrooders, will go so far as to hide the eggs in the male fish’s mouth, where they will live even after hatching. There are a few fish that do abandon their eggs to the surface as one mass, but in their case, the eggs are at least disguised as foam. These are the bubble nesters: the gouramis, the sunfishes, the Siamese fighting fish, the electric eel. The males from many of these species will, when approached by a female, begin frantically building a raft-like nest made of bubbles and bits of vegetation, glued together with saliva. But unlike the monkfish’s veil, the bubble nest is vigorously defended by the male while the young fry develop and hatch.

Though, like bubble wrap, male betta fish have trouble not compulsively popping their nest to pass the time.

So why the mysterious veil? One reason is surely dispersal; a traveling veil of eggs ensures that the babies that survive won’t grow up to live in the same immediate habitat as the mother, where they would compete with her for food, be subject to cannibalism, and possibly inbreed with her. I have another theory, as well: given the monkfish’s see-food diet, I imagine that male monkfishes — always smaller than females — would be hesitant to approach her to spawn. The externally-fertilized eggs, floating on the tide as a veil, would not only act as a sort of flag for male monkfishes to spot, but would allow them to spawn without fear of being chomped. The veil’s tremendous length would also allow several males to fertilize the eggs, increasing the odds that the fittest monkfish will be among the fathers. As for predators, the veil may simply be too big to be eaten completely; at least a few strips of fabric must survive and weave the next generation. Or perhaps the eggs are, for some reason, unpalatable. Ugly food is good to eat, and sometimes a delicate meal is just to admire.

Some content on this page was disabled on January 25, 2016 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from RandyBrogen. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

August 6th, 2011 at 10:49 pm

please post again. It’s been a month!

August 14th, 2011 at 3:02 pm

POST MORE STUFF

October 4th, 2011 at 7:42 am

it’s been two months

please post!!