Ficus. Its name is synonymous with low-maintenance, unobtrusive office plants. But in the wide Ficus genus, there are a few species of fig trees that are anything but tame. In fact, they have a predilection for death and domination. This story is about two distinctly different creatures whose lives are inextricably linked: the strangler fig and the fig wasp. It is a story about sex and murder in Florida. Mostly, it is a story about the mentality and biology of control. One of these partners-in-crime kills by slowly choking the life from its victims, and the other is its accomplice, furthering its domination of the forest with rape and incest. To be sure, you’ll never look at Fig Newtons the same way again.

The strangler figs are a loose association of banyans and vines across the New World who share a similar modus operandi. The strangler fig starts innocently enough, as a seed planted high in the crotch of a tree in a splat of bird droppings. The seed sprouts into an small epiphyte, living in the host tree and enjoying the sunshine afforded by its pleasant penthouse suite.

Soon, the harmless epiphyte is sending roots down the host tree’s trunk into the soil below. When it has touched the ground, the character of the fig takes a change towards the vicious. Its roots begin cutting into its host tree’s bark and cambium, cutting off its flow of nutrients while simultaneously stealing all it can from the soil. Its crown rapidly expands to shade out its host, starving it of sunlight. Over the course of years, the strangler fig will have not only murdered the nurse tree that nurtured it in infancy, but will have absorbed it into its own trunk for extra support. The dead body of the original tree will eventually rot, leaving the fig that took its place hollow inside, a heartless killer devoid of heartwood.

(Note: The BBC has finally caught on to us. Click the link and watch it on YouTube anyway.)

It is a ruthlessly effective technique. In the dense tropical and neo-tropical forests, sunlight comes at a premium. Most trees start from the ground up and wait for a tree nearby to fall so they can fill the hole in the forest canopy themselves. The strangler figs doesn’t hold its breath. It starts from the top and works its way down. Born with the silver spoon of sunlight in its mouth, a strangler fig doesn’t know what it’s like to wait its turn or climb the ladder. It simply kills everything that supported it, dominating the forest from above. But trees aren’t the only victims of the strangler fig’s desire for absolute control.

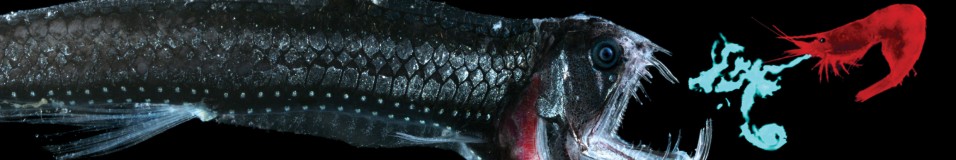

A bulb-like fig “fruit” is unlike any other in the plant family. It’s called a syconium, and it is an unusual structure in that the flowers are entirely internal. Why would a plant hide its flowers and make them difficult to reach? Precisely to control exactly who is pollinating it, and how. All 850 species of fig have a symbiotic fig wasp that specifically targets each. These wasps are so small you would barely notice them, nevermind freak out if they got trapped in your car; most can fit through the eye of a needle. This miniature stature is essential, as the pregnant female wasps will need to squirm into the tiny opening in a fig syconium — called the ostiole — an aperture so small they will break off wings, antennae, and even limbs to get in. She must enter the syconium, for a fig wasp only eats fig flesh and only lays eggs in the female flowers of her type of fig.

A monoecious fig bearing both male and female flowers inside will have not one, but two types of female flowers: those with a long pistil, which the wasp cannot penetrate with her ovipositor, and those with a short pistil, in which she deposits her eggs. The pollen she brought with her into the claustrophobic confines of the fig “fruit” dust the long-pistil female flowers and create seeds, and the short-pistil flowers will bear her children instead. Having laid her eggs and served her purpose, she dies inside the syconium. The male wasps hatch first, sniff out their sisters, and impregnate them through their eggshells while they are not even hatched. In most species, the male wasps then chew through the walls of the syconium to escape; in some species, the males are born blind and wingless and die while tunneling through in the syconium, having knocked up their unborn sisters over their mothers’ dead bodies, and never knowing anything of the world outside the dark chamber of the fig. (Eventually, an enzyme called ficin will digest the mother and sons and dissolve their bodies back into edible protein. Yet another way the fig tree devours the creatures that support it.) The females hatch a few days later, already pregnant from their brothers, and escape either by their brothers’ escape tunnels or by the ostiole. They will pick up pollen from the male flowers inside the synconium and carry it with them to their own syconium, where they will pollinate the plant, lay their own offspring, and die. The entire cycle of reproduction, self-mutilation, and insect incest happens within a tiny chamber of horrors we call a fig, and the wasps wouldn’t have it any other way.

Ecologists call this a mutually beneficial relationship; the wasp and the fig have evolved to need each other. But I cannot help but see the fig tree’s asphyxiating domination of its host tree and its almost sadistic control over its pollinator as connected. The law of the jungle is an oxymoron; in the jungle, there is no law, only chaos to be exploited. The more precise the means of exploitation — the more control you have over your enemies and your pollinators — the more success you have over the unorganized masses.

Strangler figs and humble houseplant figs both create complicated traps for their wasps, forcing them to commit acts of self-mutilation and depravity in order to achieve their ends. This level of domineering reminds me of another rainforest plant: the bucket orchid. Orchids, like figs, have very specific pollinators — euglossine bees, in this case — and have a battery of different tricks to deceive them into carrying their pollen payload. The bucket orchid doesn’t simply seduce its particular bee with sweet-smelling pheromonal perfume: it dunks it in a pitfall trap full of the slippery stuff. Unable to fly out of the “bucket” because of the liquid, the bee finds the only other exit, a narrow passageway in the flower just big enough for it to squeeze through. But the final exit has been measured precisely to the millimeter for this kind of bee, and the poor dupe becomes stuck with its head out the floral door, where the orchid detains it for hours while it attaches its pollen sacs to its back.

Once the adhesive has been set and the pollen is firmly attached, the doorway opens slightly to let the bee out… to make the same mistake again and deliver its payload. It is a machine of supreme sophistication, worthy of the most inventive torturers of the Medieval era.

This is what the master manipulator understands well: know your slave. Know its dimensions and its desires. Force it to need you. Only ever give the slave just less than enough. Make it bend and break itself to gain its desire. And always, always control its actions in a small space. The strangler fig, as a tree, has no such subtlety: it takes what it wants by brute force. It smothers, it consumes. But when it comes to sex — its pollinators’, and thus its own — it exerts a level of control that is exacting, precise, and leaves no room for error or free will. It is a sexual tyrant.

But as the wise man said, life finds a way. There is one type of wasp for every fig tree, but there are a few more species of wasp than that. They are the deviants: “bogus,” non-symbiotic wasps with extra-long ovipositors that can lay eggs in the long-pistiled flowers in the syconium that the symbiotic wasps cannot reach. If a short-pistil and a long-pistil wasp breach the syconium, all of its female flowers are destroyed, and the fig cannot produce seeds. The wasp needs the fig, but the fig benefits little from the wasp. The wasp is outside its tiny system of control. It seems that in the realm of every master, there are those who avoid the slave’s lot by refusing to play by the rules.

March 31st, 2011 at 8:59 am

Wonderful post … and beautifully written. Thank you!

March 31st, 2011 at 1:26 pm

Other than the fig wasp, there’s only one animal that’s crafty and ingenious enough to make it past the ostiole:

1.bp.blogspot.com/_dT-9EbyizNA/TUb5eZWEJyI/AAAAAAAAAL0/2z1R00iHqjk/s1600/Fig+Newtons.jpg

April 5th, 2011 at 6:08 am

Nicely written…I found this blog on a search to show my five year old a photo of an Opossum; then found this article, which I’ll be sharing with my fellow tropical plant fanatics.

Adding you to my “must read” list.

April 20th, 2011 at 1:30 pm

[…] As if all this weren’t bad enough, the pollination of the figs requires a sick act of death and incest by a symbiotic wasp species that depend on the figs for their own reproduction. Learn more about the disturbingly fascinating process in this wonderful article on The Quantum Biologist. […]

April 20th, 2011 at 2:17 pm

This is an amazing blog! As a biology teacher, I really enjoyed reading this. And oddly enough, we just talked about the mutualistic relationships between the fig wasp and the fig tree… love it!

April 22nd, 2011 at 4:11 pm

Thank you! As a biology teacher myself, I love praise from other biology teachers. Please keep reading, or feel free to toodle around in the archives for your favorite animals!