Chick flick or no, you cannot deny the greatness of the 1992 film A League Of Their Own. It’s a comedy, a history, and one of the best baseball films of all time. It’s got memorable lines (“There’s no crying in baseball!”), memorable characters, an all-star cast, and is singularly responsible for starting my lifelong crushes on both the statuesque red-headed Amazon genius Geena Davis and the totally underrated tomboy hottie Lori Petty. More importantly, it’s the only movie I know that tells the story of American women fulfilling traditionally male roles during World War II, a fairly significant turning point in the feminist movement.

I bring it up because I was recently discussing both the movie and the movement around the campfire with a co-worker. Later in the evening, another co-worker and I were discussing birds, and he told me an incredible story about chickadees. I knew that chickadee flocks work a little like wolf packs, with a few mated pairs in an alpha-beta hierarchy, plus the occasional floating loner. Usually, the death of an alpha male or female means that the beta male or female moves up the ladder to take his or her place in the alpha marriage. But according to my friend, this is not always so simple. He watched a flock of banded chickadees for a year, and noticed something peculiar: the alpha female lost her mate over the winter, and in the spring, the alpha female was singing male songs. What’s more, she passed over the beta male in favor of a socially less-desirable floater for a mate, and whenever the new husband would try to sing, the alpha female would fly over and knock him off his perch. Clearly, once she had gotten a taste of the male chickadee lifestyle and the power that confers, she was reluctant to part with it.

Between the discussion of the WWII female factory workforce, A League Of Their Own, and the chickadee story, I got to wondering: what other bird species are there in which the female wears the proverbial pants? I know that in some species, male birds take on traditionally female roles, such as the egg-incubating male ostrich. And in others, the females are showier than the males; when Belted Kingfishers go to prom, it’s the ladies who wear the cummerbund. But to see a true display of gender-bending, you need to travel to the Arctic Circle to see the breeding grounds of the phalaropes.

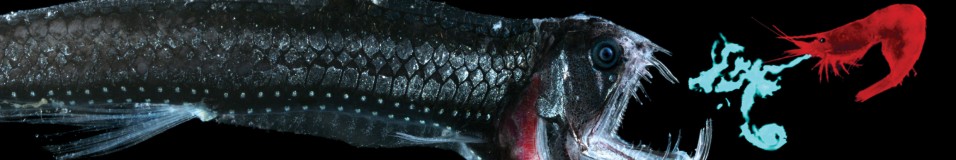

The Red-Necked Phalarope is one of my favorite birds for many reasons, not least because it shares my fondness for beef jerky and demolition derbies. It’s also one of the most charmingly madcap little shorebirds you’ll ever see, a dynamo of whirling and pecking in the water that reminds me of a children’s bath toy gone bananas. Phalaropes hunt tiny insects and crustaceans on the water’s surface, and they often swim in tiny circles which create whirlpools that raise their prey up from below. That’s right; phalaropes hunt by creating miniature vortexes. They also rely on the whirls and eddies created by larger animals, and so can be found following pods of whales, which lift tiny animals with them every time they surface to spout. The phalarope is a tiny wind-up tornado living in the shadows of whales.

Male and female phalaropes also look and behave quite differently from one another. Traditional “masculine” and “feminine” behavioral roles arise primarily from the amount of investment put into the egg. It is expensive both to produce and to care for, both in energy and in time. Because the female carries the zygote, she’s already at a disadvantage in the sexual arms race; the male has billions of sperm to spread around the neighborhood, but she has a limited number of eggs that can be fertile at a time. This makes her distinctly choosy about her mate; the male can afford to sleep with any young thing, but if her offspring are to survive and reproduce, she must make sure that the male she chooses is either the sexiest sperm donor or the most caring father, or hopefully, both. This leads to competitions between males, which often leads to aggressive personality traits. Courtship rituals such as song and dance evolved from this divide, and sexual dimorphism — the physical differences between sexes in some animals, including our own — favors brighter colors, or longer tails, or bigger horns. Meanwhile, in species where brooding duty is left primarily to the females, they protect their investment by literally sitting on it. This imbalance in parental roles tends to select for female birds who are quieter, less aggressive, and more camouflaged. It’s more complicated than that, as you’ll see, but as a rule with the birds, in almost every case in which the male and female play different behavioral roles in raising young, the male is bigger, brighter, and more extravagant, while the female dresses down in earth tones.

So if you ever see a mated pair of Red-Necked Phalaropes, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the brightly-colored one that arrives first to the breeding grounds, chases after the duller brown-colored ones and keeps a harem, fights other birds of its stripe for territory, and leaves its nesting and chick-rearing duties to its mate would be the male. But you’d be wrong. In phalarope culture, females have taken over all the traditional male roles, and vice versa: the males are the “stay-at-home dads” who build the nest, are pursued and defended by females until the egg is laid, and then stay behind to raise the chicks. (The female rather cavalierly abandons her family to migrate South immediately after the eggs are laid. Phalaropes are deadbeat moms.)

But why? Out of 10,000 species of birds, why are there only a few in which aggressive, competitive territory building and wooing is in the purview of the female and meek nest-keeping and child-rearing is left to the male? In other words, What is the root of machismo?

The question of sexual role reversals vexed no less a mind than that of Charles Darwin. Investigating the bustard-quail, an Indian bird in which the males brood the eggs and the females are so pugnacious with each other that villagers fight the hens instead of the cocks, Darwin concluded it that the answer to the masculine/feminine reversal had to be The Ratio. Ecologists use the more specific term Operational Sex Ratio (OSR), but you probably know it simply as The Ratio: it’s the moment you look around at your dorm hall and realize there are only four girls and about ten guys, and realize you are going to have to start shaving. Maybe a little aftershave, for effect. And before you know it, you are dressing a little nicer, and engaging in power struggles over the territory of the common room when the girls are present, and getting into arm-wrestling contests at parties to impress them, and maybe wearing brightly colored polo shirts that accentuate your biceps, which you start calling a “gun show.” In short, you have become a bro. THAT Ratio.

Darwin postulated that an OSR that kept males in short supply would select for aggressive, attractive, competitive females, and reward males with the luxury of choice. But there are cases of sexual courtship role reversals in bird species where there are plenty of available males, and cases of male choice of mates without competition by females. In the case of the phalarope, I suspect it’s more complicated than simply a gender ratio. For starters, all three species of phalarope share this role reversal with each other, and also with another Arctic-breeding hunt-and-peck shorebird, the Eurasian dotterel. And another, the spotted sandpiper. Of the thirty or so birds that exhibit some type or degree of courtship role reversal, it seems that a surprising number of them are in the sandpiper mold.

It might be that the males started raising the young (and vacuuming, and doing the dishes) when genetically inferior males realized they could control their genetic destiny better by being the best caretaker they could be, setting off a genetic chain reaction. But that doesn’t explain why the females lay and leave. After days of research, I’ve come to precisely no conclusions about why it has to be the male on the eggs. The only thing I can imagine is that the chilly Arctic climate equalized the sexual competition between the male and female — she has to lay the egg, but he must help incubate it if he wants offspring, and thus has less time for philandering — and something swung the pendulum in the opposite direction. Maybe it was a female phalarope somewhere back in history, high on testosterone and feeling bold, who decided to step off the eggs in front of the male just to see what he would do. “Would you mind sitting on these?,” she asked. And quickly, the male jumped on the eggs, and she took off, as if to say, “So long, sucker,” knowing that he could never leave the eggs if he wanted his offspring to hatch and survive. And survive they did, and bore bold daughters of their own, and so forth and so forth until the whole phalarope genus was made of tough chicks with a “love ’em and leave ’em” outlook on family life and males who are more docile and fussy. I don’t know it for sure, but I’d like to think that the female phalaropes took on their swagger and everything that comes with it when one brash and perhaps foolhardy bird decided to call her husband’s bluff by skipping town and leaving him with the crying babies and a sink full of dishes.

April 20th, 2011 at 8:47 am

First, I assume that you know that Geena Davis is from your home state (ok, albeit down by the Cape); I also assume you know that, like a female red-necked phalarope, she’s currently on her fourth husband… who is, to continue the comparison, smaller than she is. So, a remarkably apt allusion, all around.

Now, on to more avian matters… there seem to be two thoughts about why red-necked phalaropes engage in gender-bending in the nest. Well, three, actually, if you include the “we have no idea” school. The first model was well described by the great Harold Mayfield, who wrote, “Unreliable breeding conditions place a premium on a female’s ability to produce additional and replacement clutches, and therefore may foster female emancipation from care of eggs and young, and polyandry…” (“The Auk” 1978) Mentioned in this description of “unreliable breeding conditions” include the capricious climate of the nesting area, undependable food sources, predation by arctic foxes (whose populations swing upward and downward based on the bloody algebra of ptarmigans, hares and rodents), the unintended destruction caused by caribou moving through the nesting area, and, interestingly, the phalaropes’ low “breeding site fidelity.” (Sandercock, 1997) This doesn’t mean fidelity to a mate, but to the site itself. Simply put, the males build the site on kind of an ad hoc basis, unrelated to the location of last year’s nest, and show very little territoriality about it; they are sketchy nests in marshy areas. They are really used for only the nineteen days of gestation, and the hatchlings are expected to learn to fend for themselves gastronomically soon thereafter!

Now, the third (or second, depending on how you’re counting) idea has not been thought out all well, since it is my own. I’m trying to incorporate the observation that there is a relatively small degree of variation in the red-necked phalarope’s gene pool, plus the capacity of the female for multiple clutches sired by multiple males, the need for fairly constant warmth for the eggs, the males’ lack of territoriality and, finally, their low breeding-site fidelity… and thus, fairly crummy nests.

Is there something different in bird behavior that is influenced by multiple clutches sired by different (monogamous) fathers? I may well have this wrong, but my sense is that sibs in those clutches are half-sibs to some other clutches… but always through their X chromosomes, never through their Y. Is that true? And if it is, would it make a difference over time?